“He was the first person we had heard of from Britain to get to the coveted No. 1 in the charts, and we studied his records avidly. We all bought guitars to be in a skiffle group. He was the man.” – Paul McCartney

“He really was at the very cornerstone of English blues and rock.” – Brian May

“I wanted to be Elvis Presley when I grew up, I knew that. But the man who really made me feel like I could actually go out and do it was a chap by the name of Lonnie Donegan.” – Roger Daltrey

“Remember, Lonnie Donegan started it for you.” – Jack White

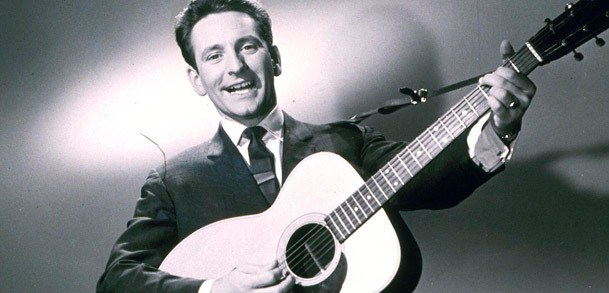

“Rock Island Line” has long been called a “traditional” tune or folk song. But in reality, the singer who made it famous – or whom it made famous — was only two years younger. Anthony James Donegan was born April 29, 1931 in Glasgow and moved to London with his family at the age of two. He grew up listening to blues, folk, jazz and American country music, and picked up his first guitar at 14. By 18 he was playing guitar around London and was a regular at the city’s jazz clubs.

He joined his first band despite a bit of a blunder: One night while on the train, he was approached by man who said he’d heard that Donegan was a good banjo player, and asked him to audition for his band. That man was Chris Barber, who’d been making a name for himself as an aspiring jazz trombonist and was putting his first group together (Still active, Barber has had a successful career in the UK. He also arranged the first UK tours of such artists as Big Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters, catching the imaginations of young British musicians like Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones).

Donegan had never played banjo in his life, but he bought one, taught himself what he could in a hurry and tried to bluff his way through. His playing didn’t get him into the band, but he hit it off with the band and found himself in. Eventually, the Chris Barber band joined forces with Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen and developed a name for themselves as they gigged around London. In between their Dixieland sets, Donegan would stage mini-sets with two other players to play his versions of blues, country and folk standards on acoustic guitar or banjo, backed by upright bass and drums. The band took to calling these “skiffle” sets on their posters, and they caught on.

In 1949, he was drafted into the British army and spent a year in Vienna, where he discovered the broadcasts of American Forces Radio Network and its broadcasts of American music. He also got to meet met U.S. servicemen, from whom he got records. When he got back to London in 1951, he found another source for blues and jazz records at the American Embassy library.

In 1952 he formed his own band, the Tony Donegan Jazz Band, and scored a spot opening at Festival Hall for pianist Ralph Sutton and Lonnie Johnson. The announcer mixed his first name up with Johnson’s that night, and the new moniker stuck.

After Colyer quite the band and Barber reassumed leadership in 1954, they recorded an album for Decca based on songs from their live set, including the skiffle numbers. Among these five tunes was “Rock Island Line.”

The album was a bigger hit than anyone expected, selling 60,000 copies, so Decca decided to release some singles. “Line” had a 22-week UK chart run, peaking at Number 8, and surprisingly, cracked the Top 20 in the U.S, where it sold 3 million copies.

British teens loved it: it was catchy, had American appeal and was a style they could easily play themselves with just a guitar or banjo, tea-chest bass and a washboard and thimble. Skiffle became the rage.

Donegan hadn’t been paid more than a few pounds for the sessions, and didn’t get royalties, but he was rapidly becoming a star. That his next single, “Diggin’ My Potatoes,” (written by blues legend Memphis Minnie) was banned by the BBC for suggestive lyrics only added to his allure with the younger crowd. He left Baker’s band and went to EMI/Columbia Records, achieving enough success to win appearances on the Perry Como and Paul Winchell TV shoes. He played on bills with Chuck Berry as well, but his missed his family and soon headed home.

He continued to create hits: “Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavor?” went Top 5 in the U.S. and skiffle solidified its place as a national craze, inspiring the likes of Cliff Richard, Tommy Steele, and in Liverpool, a fledgling group known as the Quarrymen.

But skiffle’s shelf life was short. By 1958 it was on the wane, although Donegan would continue to chart until 1962. But the early 60s saw the young rockers he inspired take over the charts, knocking skiffle aside, and Donegan with it. He continued to play, record and tour, but aside from a nostalgic craze in Germany in the 70s, his days as a top draw were done. He worked as a producer and songwriter, crafting a hit for Tom Jones entitled “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” which was also recorded by Elvis. As head of his company, Tyler Music, he had production and publishing rights to the songs of a young musician named Justin Heyward, including one called “Nights in White Satin.”

It’s a natural rhythm in popular music, but Donegan was embittered by it, and remained so for the rest of his life. He resented the “long-haired, pot-smoking pop musicians,” saying “The Beatles’ first records were archaic rock and roll, and I was resentful at the way they stopped my cash flow.” He complained constantly about his lack of remuneration for the “Line” sessions, conveniently forgetting to mention that he’d profited tidily from arranger credits for quite a few folk songs, as well as the royalty deals he’d aggressively pursued. Even his daughter described him as a whiner. By all accounts, he wasn’t a pleasant person, despite his cheery, folksy stage image. Perhaps this contributed to his poor health: He suffered from several heart attacks beginning in the 1970s.

With thanks to Charles Crossley (@cvcjr13) for the link, an example of Donegan’s pettiness, again with regard to Justin Heyward: http://www.justinhayward.com/justin-great-yarmouth/

But his temperament didn’t detract from the affection of the many performers he’d inspired. In 1978 Rory Gallagher, Brian May, Ringo Starr, Ron Wood, Elton John and Peter Banks joined him for the album “Puttin’ On the Style,” featuring new versions of his classic hits. Macca wrote the liner notes for his last album, “Muleskinner Blues,” and Mark Knopfler paid tribute to him upon his passing with the song “Donegan’s Gone.” Peter Humphries’ 2012 biography, “Lonnie Donegan and the Birth of British Rock and Roll,” featured contributions from Van Morrison, Knopfler, Macca, Bill Wyman, Brian May and Richard Thompson. Daltrey, Townshend and Page have given credit to Donegan and skiffle for their beginnings.

More recently, “Downton Abbey” actor Jim Carter made a documentary about his hero that included footage of a 16-year-old John Lennon playing Donegan tunes with the Quarrymen.

In the late 90s, a few compilation albums were released, and Donegan still toured on the nostalgia circuit. It was on one such tour that he suffered his final heart attack and died on November 3, 2002 near Cambridge, England.

Over the course of his career, Donegan notched up 31 Top 30 UK hits, 24 of them successive, including three Number 1s. He was the first British performer to have two songs in the U.S. Top 10 simultaneously. He received the Ivor Novello Lifetime Achievement award and was made an MBE in 2000. In his own estimation, his greatest achievement was making folk music popular again. The year of his death, he told the Newcastle Journal “In England, we were separated from our folk music tradition centuries ago and were imbued with the idea that music was for the upper classes. You had to be very clever to play music. When I came along with the old three chords, people began to think that if I could do it, so could they. It was the reintroduction of the folk music bridge which did that.”

(An interesting side note: Donegan’s son Peter is himself a musician who appeared in early 2019 on the UK version of “The Voice.” One judge turned around for him: an excited Tom Jones, who performed “I’ll Never Fall in Love” with him).

George Harrison said of him, “If there were no Lead Belly there would have been no Lonnie Donegan; no Lonnie Donegan, no Beatles. Therefore, no Lead Belly, no Beatles.’” In inspiring untold numbers of British musicians who themselves remade rock and pop music history, Donegan changed the face of popular music.

At one time, his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame might’ve drawn a Who’s Who of British classic rock and made for a show to remember. Who knows—maybe if Mark Knopfler took part or was even given the opportunity, he’d have fonder feelings about the Hall and the debacle of 2018 would’ve never happened. Jack White would have made for a compelling link to newer music. Now, an all-star jam like that isn’t in the Hall’s desired demographics. But all that doesn’t matter: any way you look at it, the King of Skiffle should be enshrined.